But Is It Music?

How Simon Steen-Andersen Reinvents the Composer’s Craft — Again

In November 2025, the iconic Akademie der Künste building on Hanseatenweg became both a musical instrument and a stage set. Composer Simon Steen-Andersen premiered Run Time Anomaly, a site-specific performance featuring teenage dancers from the Youth Dance Company Sasha Waltz & Guests. But what is this — a film shoot? An installation? A dance production? A concert? And why is the person in charge still called a composer? Music critic Alexey Munipov reflects on how composers stopped being satisfied with sounds alone and began to include everything around them in their scores.

A slender man in a white shirt, a microphone in his hand, runs through a building filled with objects. A camera follows him. On the run, he sets off a chain of reactions and records it all — he knocks on walls, sends a plastic bag up into the air, drops something, stomps. What comes out is a wildly brisk, unexpectedly cheerful and intricate-sounding piece — a kind of time machine made of steps, rustles and impacts. This run resembles a domino effect, a Rube Goldberg machine and a sound parkour — and yet it is a modern composition, conceived and realized by a composer.

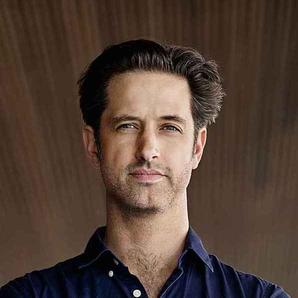

Simon Steen-Andersen (b. 1976) is a Danish composer known for boundary-pushing, transdisciplinary works. Trained in classical composition, he nonetheless works between the categories of music, performance, theater, choreography and film, often taking on the role of stage director in his projects. In Run Time Anomaly, Steen-Andersen not only constructed the piece’s sounds but also co-choreographed it and created its video design. The work literally inhabits the building: the performers trigger sounds by interacting with the architecture, and their movements are amplified into the musical texture. The project grows out of ideas he developed across his long-running Run Time Error series, where filmed actions in distinctive locations turn the built environment into a protagonist, an instrument, scenography, and even compositional form.

In an interview for Seismograf, a Danish magazine about new music and sound art, Steen-Andersen states very clearly: “Even though I take on different roles, make videos, stage different things or concern myself with movement sequences, I am still a composer. I am not going to suddenly become a film director or a video artist”. He continues: “For me, it is about integrating the different elements, not so they are just layers on top of each other but in a way where they are truly integrated, so you do not have the meeting of two elements from two different worlds, but instead you have one element that belongs in both worlds”.

Traditionally, a composer is understood as someone who works with sounds. Or is he?

Homo Componens

The original meaning of the word “composer” was not confined to music. It's etymology goes back to Latin "componere" — “to put together; to assemble.” In Old French, composer meant “to put together, arrange; to write (a book)” (12th c.). By the late 15th century, English compose also meant “to make or form by uniting two or more things” — a sense that extends beyond sounding matters.

As composer Vladimir Rannev explained in an interview for my book Fermata. Conversations with Composers: “‘Composer’ literally comes from ‘to assemble’; in many ways it’s a purely technical profession. You can even assemble tonight’s dinner menu.”

And indeed, work with more than sound was part of the composer’s job description. Even in classical Greece, mousikē meant an integrated practice — poetry sung/recited with dance and movement; the tragic chorus literally sang and danced. That makes “music + movement” the original norm rather than a late aberration. In the Renaissance, composers frequently wrote applied music for ceremonies of all kinds, and the courts where they worked were laboratories for sound, dance, machinery and perspective. The Florentine Intermedi for La pellegrina (1589) are a key forerunner of composerly thinking that “writes for” space, bodies, and devices. Early Parisian court spectacles of the 16th century and the English masque of the early 17th coordinated song, dance, poetry, moving scenery, lighting illusions and more — with composers at the center of the action. Venetian cori spezzati in the 16th and 17th centuries, written by Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli, worked with spatially separated choirs within San Marco’s architecture — using space as a notated parameter.

Later Baroque site-specific commissions — Handel’s Water Music (1717) and Music for the Royal Fireworks (1749) among the best-known — were tailored to the open air and could include anything from barges to artillery salutes, along with light, smoke, distance, a moving audience.

Color, Noise, Total Art

Long before contemporary multimedia, composers dreamed of uniting art forms. In the early twentieth century Alexander Scriabin pushed past sound into the realm of light and color: his Prometheus included a part for a color organ so that hue itself became, in principle, composable. Mysterium, his unrealized magnum opus that would fuse music, light, dance, scent, and architecture in a grand spiritual ritual, is an extreme conceptual precursor to the multimedia performances of today.

Around the same time, the Futurists reimagined music’s substance: Luigi Russolo’s The Art of Noises pushed urban clatter into the concert. While not “multimedia” per se, the Futurists events expanded the sonic material of music and filled performances with a provocative performative energy — a first step toward treating the act of producing sound as spectacle in itself.

It was in the mid-twentieth century that the live event itself became a primary material. John Cage reframed the concert as theater; 4′33″ isolates the act of presenting, while the early happenings — like Theater Piece No. 1 (1952) — explored mixed media: Cage treated the event’s collage of sound, movement, visual art (Robert Rauschenberg’s paintings were hung from the ceiling), and even smell (coffee was brewed) as one composition unfolding in time. While Cage and Fluxus events were more about concept and process than polished spectacle, they established the notion of the composer as an event-maker rather than just a note-writer. Music could be “composed” with anything, not just musical tones.

Mauricio Kagel, an Argentine-born composer who lived in Germany, forged instrumental theater: scores where musicians act, mime, re-stage the rituals of classical performance, and play with objects, layout, even facial expression. The new genre also emphasized that composers could be stage directors of their own music, broadening the composer’s role. This line of thought directly shapes Heiner Goebbels, who treats text, bodies, light, stage and sound as co-equal voices and composes the entire production process with collaborators in rehearsal until image, movement and music lock.

The Composer Returns

Many modern composers routinely work with electronics, sensors, video and choreography; Alexander Schubert turns gesture into data that drive sound and light, Michel van der Aa authors stage and screen from the same desk. They fold light, electronics and moving image into their work so seamlessly that credit lines start to blur. Are they directors? Multimedia artists? Simon Steen-Andersen is firm on this point — “I am still a composer”. However unusual the surface, his gestures are grounded in tradition. Is it music? Yes, as long as he composes the whole situation. Besides, the logic behind the project is definitely musical.

“The idea of Run Time Anomaly comes out of a series of site specific audiovisual performances,” he explained to Voices.Berlin. “It always works with the idea of documentation through different perspectives — mostly the perspective of music. It’s about going to a place, and organizing what I find in this place — in a musical manner. Using this space as an instrument, but also showing the instrument.”

His approach may seem radical, but in reality it inherits as much from Kagel, Russolo, and Cage as from the large-scale Baroque experiments or the Venetians Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli’s work with spatial sound. Sound is not just dots on staff paper; it is vibration that permeates everything around us. There is simply nothing soundless in the world — and a composer, even the most modest one, knows that their material is the entire observable universe. Having mastered the handling of sounds — those strange, multiple phenomena surrounded by a cloud of overtones, feelings, emotions — a composer is able to assemble their compositions out of anything, even from such a restless material as the teenagers of Sasha Waltz’s troupe.

Related Events

8. November um 20:00

9. November um 18:00